If a memoir were to be written about the Internet and social media in 2015, it would be entitled The Big, Bad World against Poor, Helpless Me.

Or something snarky about the constant need to be outraged or offended by something new on any given day.

This week’s topic has been Target’s decision to remove gender-specific signage from their toy department. And the reaction has been intense. Many have been in favor of the changes, while others have been concerned that Target’s decision is yet one more move away from a traditional, binary understanding of gender.

I’ll be completely transparent and say that Target’s decision doesn’t really bother me. Regardless of what signs in store toy departments suggest, I have encouraged my children to be interested in what they are interested in. If my son wants to cook, that’s fine with me. If my daughter wants to drive Hot Wheels cars, I see no problem with it. If my son wants to sleep with a purple, unicorn Pillow Pet, that’s cool with me.

The suggestion on the sign doesn’t influence the way I parent my children.

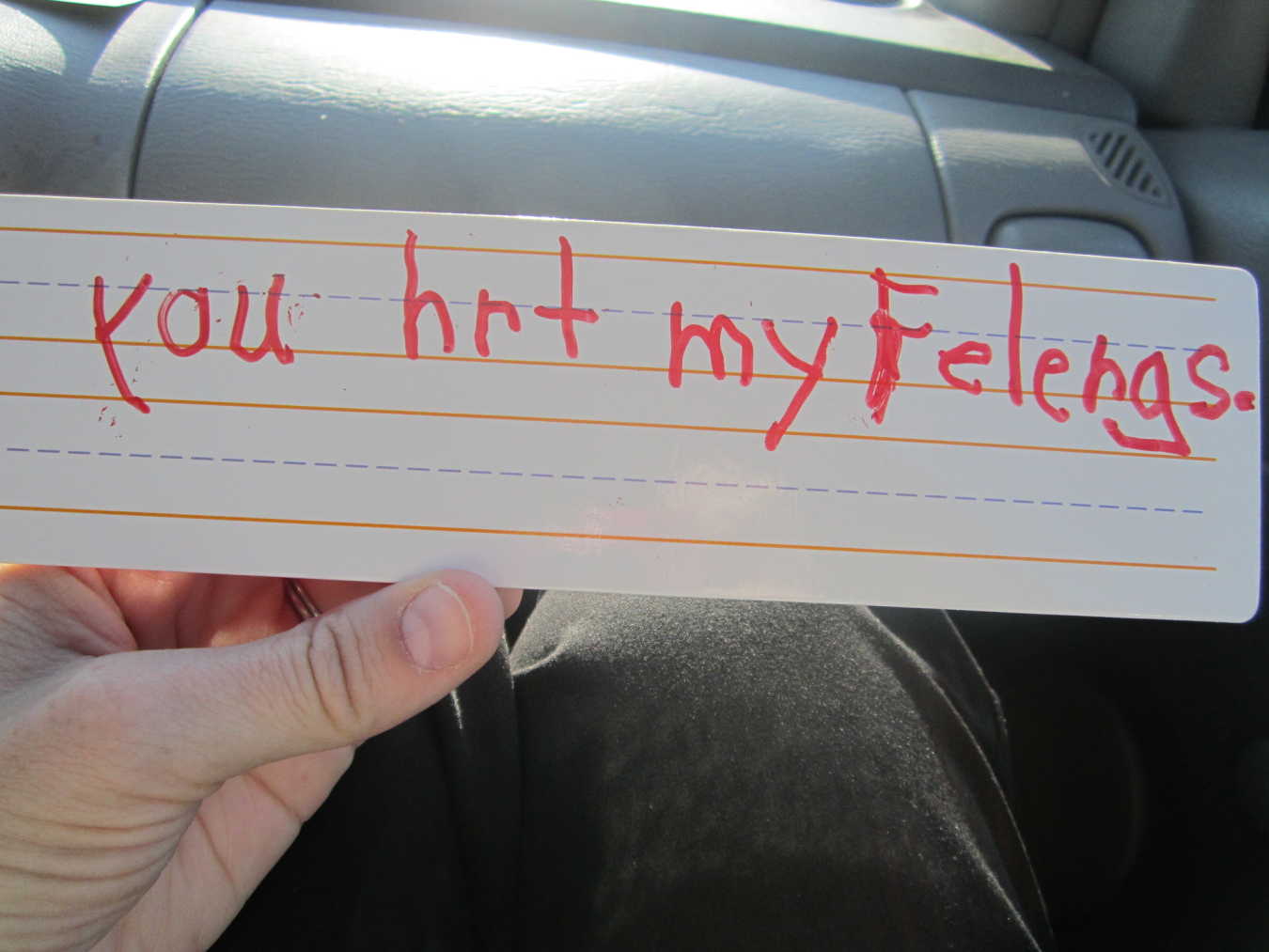

However, as my kids have begun learning to read, they have asked me questions about the things they read on store signs. They’ve flushed with embarrassment at the realization that a toy they love was designated as a toy for the opposite sex. I’ve tried to use those moments as teaching opportunities, even though I’m a floundering mess most of the time. Despite all my efforts, I’m still very much a parenting work-in-progress, just trying not to leave my kids with too many issues they have to work out in therapy.

The question that I’m wrestling with in the wake of Target’s decision- and the subsequent conversations about toys and gender – has very little to do with toys and the way kids play. The part that I’m puzzling over is the intensity of the reaction to this change, and other changes like it.

What is it about Target’s decision that has so many people either overjoyed or furious?

While I suspect that each person’s reaction comes from a mixture of beliefs and personal experiences, I also wonder if something more is at play.

I wonder if part of the visceral reaction has to do with the stage of life our society is in. I have explored before the idea that the church in the United States might be in a state of prolonged adolescence, in part because many scholars have suggested that the United States as a whole has much in common with adolescence. And, I wonder if the conflict of adolescence might be one piece of why Target’s decision has caused such an intense response.

In adolescence, we begin to figure out who we are by figuring out who we are not.

In Erik Erikson’s stages of human development, each stage has a central conflict. For the adolescent stage, the primary conflict is about identity. The two extremes are role rigidity and extreme diffusion. A healthy identity is somewhere in the middle, and it is something that is true of us no matter our situation or context.[1] Erikson also suggests that it is during this stage of life that ideas about gender roles become internalized.

Can boys like pink? Should girls have short hair? Is it acceptable for a boy to be on the cheerleading team? Can a girl be assertive?

Whether we realized we were doing it or not, during adolescence we made decisions about what kinds of things are acceptable for boys and girls to do. As we were coming to understand our identity, we (in part) defined ourselves by what it was acceptable for us to do as young men or young women.

When Target decided to remove gender-based signage from its toy department, many people perceived it as a challenge to their deeply-held understanding of gender roles. And, threats to our identities have to be fended off. Otherwise, we face an identity crisis. Can our identities withstand the pressure, or will we be forced to change?

In adolescence we learn to define ourselves in comparison to others. We outgrow the box we were in, and we begin to wonder what we fit into instead.

In adolescence we also learn that identity is not boundless.

As a high schooler, I remember a few friends talking about anarchy. Government was too oppressive. They wanted us to fit into little boxes. Rather than give in and fit into those boxes, these friends believed the best option was to have no boxes at all. Instead of oppressive government, there should be no government.

In adolescence, we are faced with two competing opposites: the desire to rigidly define ourselves (often in comparison to others), or the confusion of being unable to define ourselves at all. Erikson believed that the successful navigation of adolescence was somewhere in the middle. Roles and identities were not rigid, but they were not boundless either.

One aspect of the outrage about Target’s decision is the fear that soon gender will have no meaning at all. I have read many concerned comments about “the government trying to make us all androgynous” or “being forced to believe there are no differences between boys and girls.”

The fear is that we’ll go from a society with rigid definitions about gender roles to a society with no definitions at all.

But, if we are to successfully navigate adolescence as a society, we need to find our identity somewhere in between rigidity and boundlessness.

The key is having an identity that stays the same no matter our context. This identity is the constant that anchors us. I think this is a large part of why many churches talk about baptismal identity as our truest identity. For Christians, no matter where we go or what changes around us, our identity as children of God is something that stays constant. And, for those who do not identify as Christians, a healthy sense of identity will still have a constant, even if that constant is something different than what is constant for a Christian.

Target changing their signs doesn’t really change who we are. It’s a peripheral change in one store that may or may not be tied to other changes in society. The key for navigating these changes (no matter whether we think they are positive or negative!) is a healthy sense of self that can withstand whatever changes might come our way.

The answer to who we are cannot be found in the toy aisle at any department store. Our identity isn’t color-coded in blue or pink for easy identification. We are not the labels placed on us by society.

Who we are is something much deeper, longer lasting, and constant. If we are to navigate our society’s prolonged adolescence we need to find that constant and find solace in it.

————————————————————–

[1] James E. Loder, The Logic of the Spirit: Human Development in Theological Perspective, p. 207.

My Thoughts