I’m Reformed, but I don’t consider myself a Calvinist.

These words cannot be used interchangeably. They do not always mean the same things.

Reformed theology encompasses a wide theological tradition, and its practice looks very different from denomination to denomination, and from church to church. The word reformed as a modifier simply means that a particular church or denomination finds its beginnings after the protestant Reformation. It is also a theologically descriptive word that can give you some clues about the way the church or denomination views God, humanity, the Bible, the church, and the world.

The word reformed does not mean 5-point Calvinist, legalist, exclusivist, or elitist.

Reformed is a way of describing a view of God and how God interacts with the world that holds onto theology with a loose grip. We are not God. We are imperfect. We need a Savior. And we need each other.

The main trouble with writing a post on what it means to be reformed is that reformed theology means different things to different people. For some, 5-point Calvinism is Reformed theology, when in reality 5-point Calvinism is representative of only a very narrow swath of reformed Christians. The best I can offer in this article is my reflections on what the Reformed tradition means to me, and some resources for further reading.

First, for the sake of clarification, it is important to recognize that the so-called 5-points of Calvinism are found nowhere in the writings of Calvin. They were written more than 50 years after Calvin’s death in the Canons of Dort.[1]

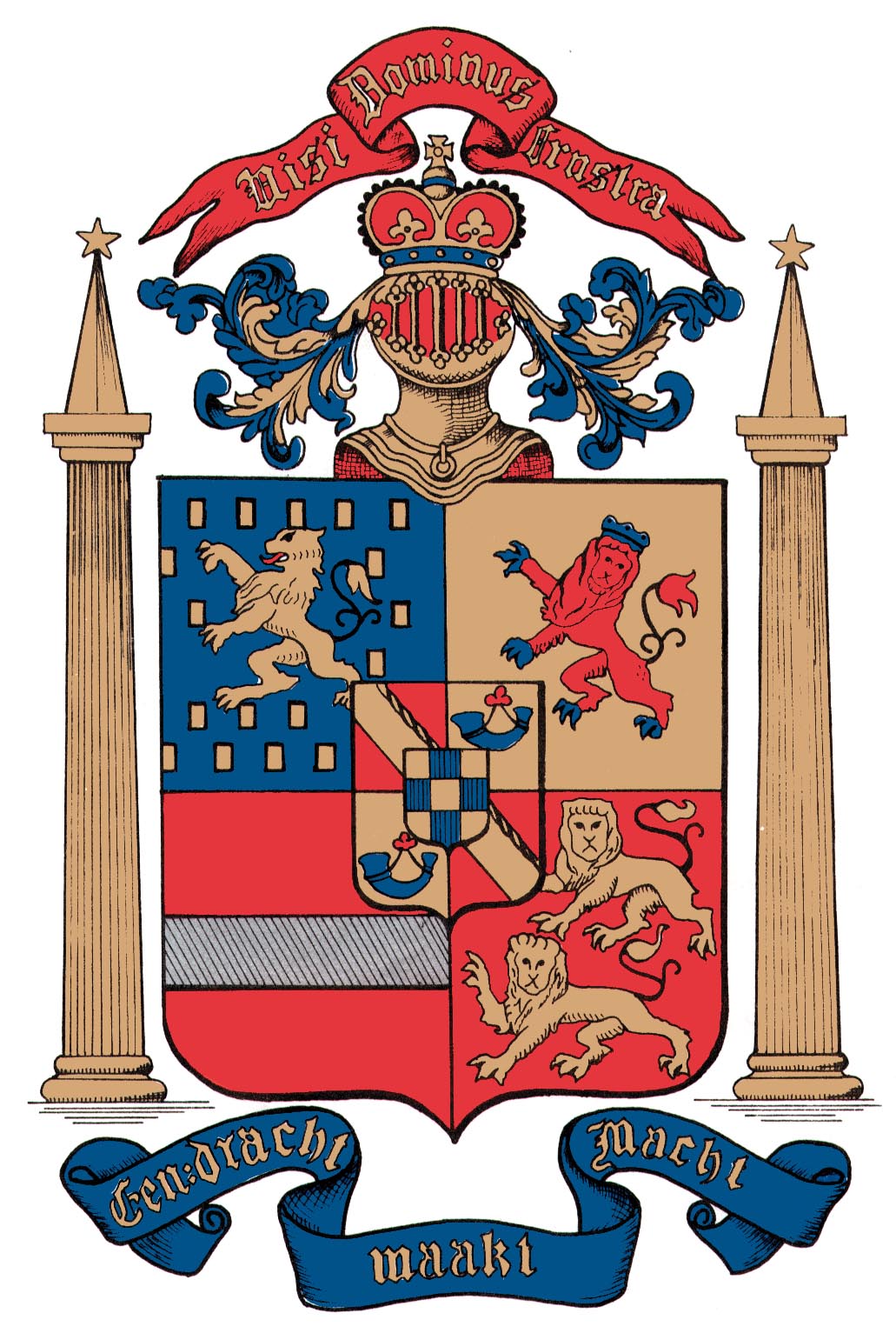

Second, John Calvin is not the only reformed theologian that inspired movements in the reformed tradition. Movements in the reformed tradition have focused on the works of Martin Luther, Ulrich Zwingli, Martin Bucer, Abraham Kuyper, John Calvin, and so many others.

I want to present some distinctives that hold true (for the most part) across the gamut of Reformed theology.

1. Reformed Theology Begins with God

Whereas some theological traditions begin with an understanding of human sin and human choices, reformed theology begins with God. God is sovereign, which simply means that God is in control. Unfortunately, the doctrine of God’s sovereignty can be abused to portray God as some kind of micro-manager, or puppet master, but the doctrine of God’s sovereignty is supposed to be one that gives us comfort.

God’s sovereignty means that nothing in this world is more powerful than God. It also means that it’s not up to me to save myself. In Reformed theology, it is God who acts first, choosing us, loving us, saving us before we’ve ever had the opportunity to earn it. It is for this reason that congregations in the reformed tradition (though there are Reformed Baptist congregations that do not) practice infant baptism. Baptism is seen as God’s first action that does not hinge upon our worthiness.

One of the biggest issues most people I talk to have with reformed theology is the doctrine of predestination. Predestination is a belief that, before the foundation of the world, God chose who would be saved. So-called “double predestination” claims that God also chose from before the foundation of the world who would be damned. In I. John Hesselink’s helpful book On Being Reformed, he cautions against taking on this idea without understanding the purpose behind it. For John Calvin, he was “trying to show why some people believe and others do not” (p.. 38). Calvin was attempting to understand how God could be in control, be the first initiator in giving us the gifts of grace and faith, and how despite all of that, some people still did not believe.

For Calvin, predestination was both his attempt at understanding passages like Romans 9-11 while also ensuring that God remained fully sovereign.

I want to be transparent and say that the doctrine of predestination is a tough one. And, I do not hold to the concept of double predestination. What is important in the doctrine of predestination is that we are not saved through our works. God is the initiator. And, as Hesselink points out, “The real purpose of the doctrine – at least as far as Calvin was concerned – was to magnify the sovereign, free grace of God. God’s grace is dependable” (p. 41).

Predestination is not about who is in and who is out. It’s about salvation being a gift of grace, freely given by God. And, human beings are not in a position to determine who is saved. Predestination is a human attempt to understand the mind of God, which can be problematic, flawed, and incomplete. The important part of this belief is that salvation is a gift, freely given, by God who is the initiator.

Not all reformed denominations fixate on predestination, but nearly all reformed bodies do begin with God as the primary initiator rather than on our own attempts to connect with God.

2. Reformed worship centers on Word and Sacrament

Even though the reformed tradition believes the articles of the Apostles Creed and also has confessions that are seen as helpful tools in understanding Scripture, the Bible is our rule.[2] What this means is that church tradition is not on par with Scripture. Our experience in creation is not on part with Scripture.We can learn about God in ways other than Scripture, but Scripture is our guide, and “it is as if the Word were eyeglasses, Calvin says.” [3] But, apart from the work of the Holy Spirit, we cannot make sense of the Word at all.

The Holy Spirit guides the reading of Scripture so that we can understand it. And the work of the Holy Spirit helping us understand the Bible is a gift from God. The Bible is not just a collection of lifeless words on pages. We believe that, “the word of God is living and active” (Hebrews 4:12). My particular branch of the reformed tradition holds that the Bible is “authoritative in all that it intends to teach.”[4]

And so, the reading of the Word, and reflection on it in the form of a sermon or homily is almost always in the center of a Reformed worship service. And, in close proximity to the Scripture are the sacraments – the Lord’s Supper/communion and baptism.

Sacraments are signs and seals of God’s grace (Plantinga, Jr., p. 113-114). They are visible actions that display an invisible reality. And sacraments are considered a means of grace. Something happens when we participate in the sacraments, something sacred and mystical.

In our baptism liturgy, the minister says these words, “Baptism is the sign and seal of God’s promises to this covenant people. In baptism God promises by grace alone: to forgive our sins; to adopt us into the Body of Christ, the Church; to send the Holy Spirit daily to renew and cleanse us; and to resurrect us to eternal life. This promise is made visible in the water of baptism.” [5] Baptism is an outward sign of God’s covenant, of God taking the initiative in having a relationship with us, and of our adoption as God’s children.

At the communion table, there is a diversity of thought in the reformed tradition. My particular branch of reformed theology is more in line with Calvin’s works. In this view, there is somehow a real presence of Christ with us. Christ is the host at the table, and something profoundly spiritual happens when we participate in the meal. The elements, in and of themselves, are not transformed into the body and blood of Christ. But, they are not merely symbolic either. Words fail when we try to describe what happens during communion, and so theologians like John Calvin and Guido De Bres talked a lot about mystery (Plantinga, Jr., 117).

3. Reformed Christianity Is Community-Oriented

In Heidelberg Catechism Question & Answer 54, we read this:

Q. What do you believe

concerning “the holy catholic church”?

A. I believe that the Son of God

through his Spirit and Word, out of the entire human race,

from the beginning of the world to its end,

gathers, protects, and preserves for himself

a community chosen for eternal life

and united in true faith.

And of this community I am and always will be

a living member.

This statement isn’t one about predestination, in-crowds and out-crowds. What we affirm in this part of the catechism is that we are called into community. The Christian faith is not an individualistic pursuit. And, this is important for several reasons. We interpret Scripture in community. We worship together. We fellowship together. We are a body.

And, we can’t mess up so much that we lose our place in this community, because it’s all about God, and not about us.

As I mentioned above, the reformed tradition is about holding on to our theology with a loose grip. This is precisely because we are part of a body – both as reformed Christians, and as part of the wider body of Christ – and we may well wake up one day and realize that we’ve gotten things wrong, and are in need of re-forming.

One of the most revolutionary ideas to me in reformed theology is semper reformanda – always reforming. The church is to be “reformed and ever reforming according to the Word of God.” We are not reformed and stuck the way we are. We are to be a discerning people, a people of the Holy Spirit, a community of believers moving along with the continuing movement of God.

This is a crash course on a few of the differences between 5-point Calvinism and Reformed theology. There are other differences such as views on atonement that perhaps will be better addressed in a separate piece.

For further reading, here’s a link to my piece over at That Reformed Blog: “I’m Not That Kind of Reformed.”

For my readers that identify as Reformed but not 5-point Calvinist, feel free to share some of your favorite resources in the comments.

—————————————————————————————-

Resources for Further Reading

(Note: I find Hesselink’s book to be the most helpful on laying out what it means to be Reformed. Plantinga and De Moor’s books are also helpful. I do not endorse or agree with everything in any of these books, but they are good starting points. For a more nuanced look at my particular denomination, check out some of the links below.)

- [1] I. John Hesselink, On Being Reformed, 1988, p. 89.

- [2] Robert De Moor, Reformed: What It Means, Why It Matters, 2001, p. 29.

- [3] Cornelius Plantinga, Jr. A Place to Stand: A Reformed Study of Creeds and Confessions, p. 49.

- [4] This phrase appears in The Church Speaks: Papers of the Commission on Theology, Reformed Church in America, 1985.

- [5] Worship the Lord: the Liturgy of the Reformed Church in America, 2005.

Some Helpful Links