In my very first class at seminary, I was presented with the seminary’s inclusive language policy. The policy urged students to make every effort to use gender-neutral or inclusive language when speaking about humanity as a whole. Faculty committed to doing the same thing in both their lectures and in their writings.

The whole concept of inclusive language was strange to me. I had never been part of a church that intentionally used inclusive language. And, I thought it was obvious that “man” meant “everyone.” The Bible translation I was most comfortable with used “man” and “men” all the time in ways that I thought were clearly references to both men and women.

I thought the whole thing was silly, but as a student who never wanted to disappoint her instructors, I decided I could abide by the policy for three years.

Not long after, I noticed myself squirming when reading books and articles for class that were not written with inclusive language. I started noticing times when “man” or “men” were used intentionally to exclude women. It began to bother me how often sermons addressed the men in the room and left women with nothing.

At the root of my discomfort was the basic, and tenderly important question: As a woman, is the Gospel good news for me?

Is Jesus for me?

Is the Bible for me?

Is there a place in the church for me?

As I began making a more concerted effort to be intentional about the words I used – both in speech and in writing – I realized how much power language has. More specifically, I realized how much power Bible translators have. Every decision about how to translate every word in Scripture has the potential to radically change how a verse is interpreted. When using the word “man,” have we obscured Scripture’s more inclusive intent? When moving away from gender-specific language, have we lost other important elements of the original text?

I struggle with this on a nearly daily basis as I read and interpret Scripture. I struggle as I put together sermons to make sure that I am not reading my own worldview into the worldview of the Bible. Much of the time, I can understand why certain translations that aim for inclusiveness use the words they use. And, I know that – in my very limited understanding of Greek and Hebrew – my understanding of the nuances of the biblical languages pales in comparison to the understanding of people who have devoted their lives to the accurate translation of Scripture.

By no means do I want to discount the difficult work that is done by translators who are so much more knowledgeable about these things than I am. What I do want to lift up is the struggle of inclusive language – the necessary, painful, difficult struggle to be faithful.

This week, I’ve been studying Hebrews 1:1-4, 2:5-12 for Sunday’s sermon, and I keep getting stuck on the translation of Psalm 8 in the NRSV. Hebrews 2:5-8a says this:

Now God did not subject the coming world, about which we are speaking, to angels. But someone has testified somewhere, “What are human beings that you are mindful of them, or mortals, that you care for them? You have made them for a little while lower than the angels; you have crowned them with glory and honor, subjecting all things under their feet.”

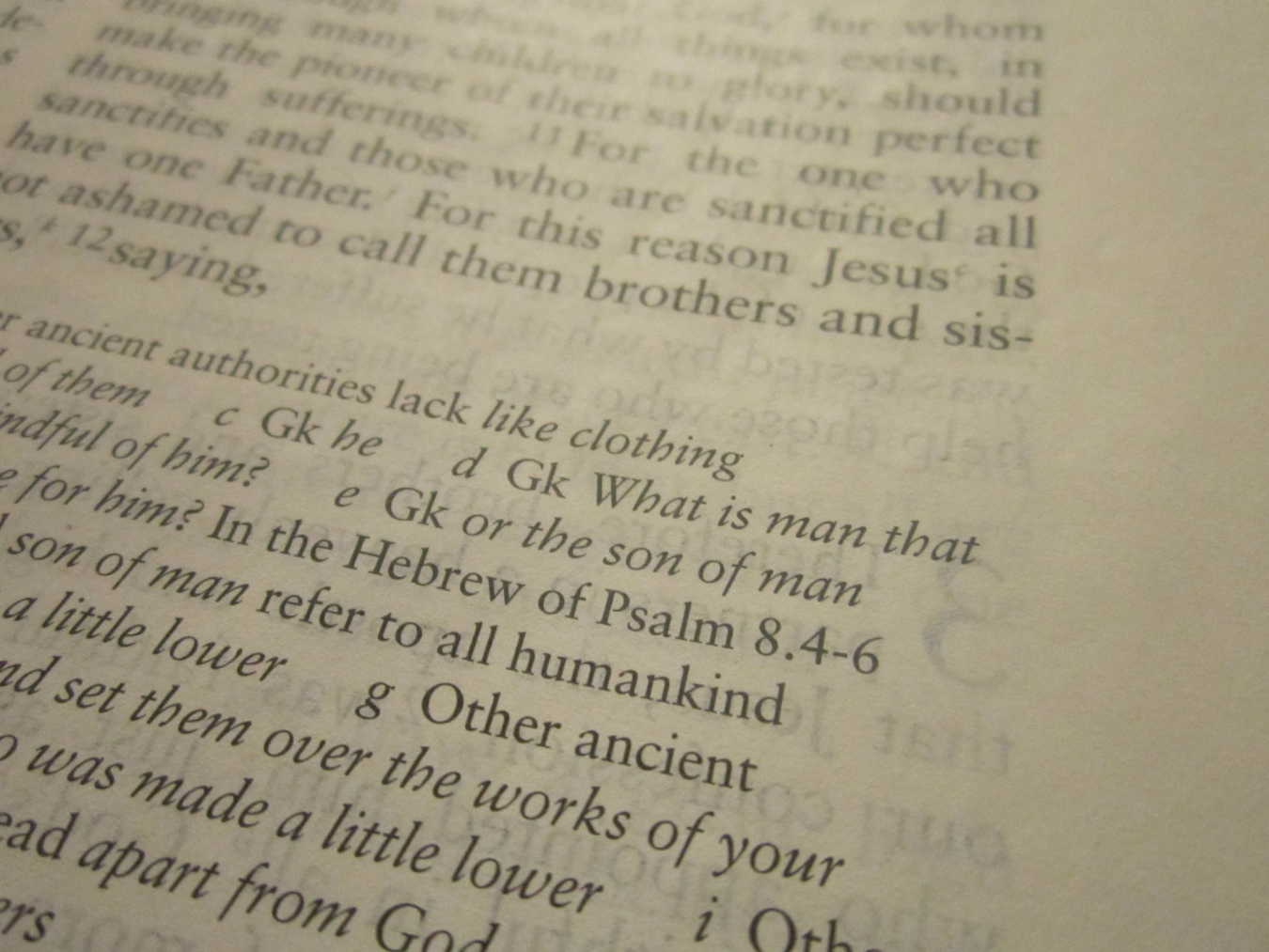

This quotation sets the stage for a vivid and theological description of the incarnation and suffering of Jesus before his exaltation. The plural “them” in the quotation from Psalm 8 seemed quite strange, so I took a look at the footnote in my Bible. It notes that the word “human beings” is “man” in the Greek, and “mortals” is their translation of “son of man” from the Greek. And then they add this as commentary along with the footnote: “In the Hebrew of Psalm 8:4-6 both man and son of man refer to all humankind.”

Here’s the question I wrestle with when preaching on a passage where the original Greek has been made gender inclusive: what was the original intent of the text? Sometimes the intent is clearly more inclusive, and including more expansive words is helpful to make sure that the original intent is not lost in our exclusive language.

In this particular instance, the intent is difficult to ascertain. Hebrews is a cosmic, theological, expansive book of Scripture that defies simple interpretation. It draws heavily off of imagery that would make sense to audiences familiar with the intricate sacrificial system of the Old Testament, and much of the connections and descriptions are lost on a 21st century, Christian audience.

The original text in Psalm 8 seems pretty straightforward. The psalmist speaks personally about the grandeur of creation, and about a feeling of awe that, somehow, God cares for human beings – who are quite small in the grand scheme of things. I can see, and understand, the decision to make “man” and “son of man” inclusive in this instance.

But, what about how the author of Hebrews is intending to apply this text? Though, in the original psalm, the text has a more universal application, does that universal application hold true in the context of the book of Hebrews?

To be honest, I’m not sure.

If one uses a gender-inclusive translation in Psalm 8, one almost has to use the same translation in Hebrews 2, or the quotation is lost. On the other hand, choosing to use inclusive language in Hebrews is making a different theological claim than if the more gender-exclusive “son of man” is used.

As I’ve been grappling with this passage from Hebrews, I have come to believe that the author is quoting from Psalm 8 to make a startling claim about Jesus: the One who is “the exact imprint of God’s very being” (Hebrews 1:3) and who is, by nature, not below the angels or anything in creation, was made lower for a little while so that he might become like all of us.

A gender-inclusive reading of the text from Hebrews is not necessarily wrong. In some way, the suffering of Jesus is suffering we are united in, too. In some mysterious way, the exaltation of Jesus is also a promise for us. The world, and the universe, and the stars, and the cosmos are all so magnificent that we can all join our voices together and ask, “What are human beings that you are mindful of us?”

But, in claiming to know that the author of Hebrews intended this quote to be applied universally to all of humanity, have we lost something in translation? Do we miss the connection to Jesus?

If we’ve lost something, is there a way to convey what we’ve lost to those who are unable to go back to the original texts and find meaning?

I am all for gender-inclusive language in Bible translations. I believe that Scripture has bold and beautiful promises for both men and women alike. I know that exclusive language builds walls where there were supposed to be bridges. It creates bondage where there was intended to be freedom. But, when we get to passages that are very difficult to understand, what are we to do about gender-inclusive vs. gender-exclusive language?

I honestly don’t know.

It’s a sticky wicket, indeed.